“Stewards of Pachamama (Mother Earth) in Guatemala: Transnational mining corporations bring devastation”

In order to learn about the situation firsthand and foster cross-cultural exchange as part of our case study, a group of us travelled to San Miguel Ixtahuacán, five hours from Chimaltenango, Guatemala, where we are students in the International Peoples’ Health University course.

San Miguel Ixtahuacán is the community where the Goldcorp Corporation’s subsidiary, Montana Exploradora, operates the Marlin gold mine. From the road, we could see an immense crater where trucks and earthmovers are extracting ore in search of gold. To the side, a large lagoon comes into sight, full of cyanide-laced water and other mining waste, to the eye in balance with nature, since there are trees planted all around to mask the wasteland. This tailings pond is a time bomb that is polluting the water, air and land. The river is a cyanide-brown, there is a metallic odour in the air and the vegetation struggles vainly to grow.

The dust blows down the roads to the surrounding towns, while the pavement is a sign of the developmentalism being broadcast from ads painted on walls of marketplaces, groceries and even public buildings. The mining corporation logo is so ubiquitous that the locals hardly notice it anymore; it’s become just another feature of the landscape. Alcohol is another common element in the markets and on the streets. Something much harder to see, given how little time we had to get to know the communities, is how different Maya groups in Guatemala are losing their cultural identity.

We found that mining in this area is having these effects:

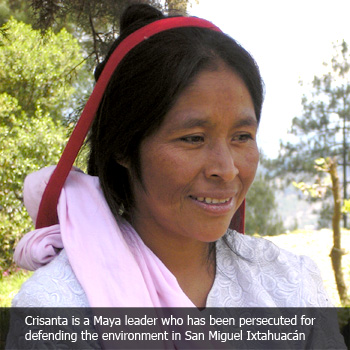

- The outlawing of protest, of which Crisanta’s case is only one example. This mother of seven children was jailed for fighting power lines from the mining company on the land where she lives. The community has mounted the campaign We are All Crisanta to defend Crisanta from the charges against her.

- Devastation of nature—pollution of the water, air and land.

- Resistance by native peoples who are a symbol of life.

- Division in the communities and areas surrounding the mining company’s operations.

- Health problems, including skin diseases and psychological disorders.

Carmen Mejía, an indigenous woman from ADISMI, an organization that supports this struggle, particularly the women who are involved, told us that protest has been outlawed and that there has been persecution and threats. “For 22 April, Earth Day, we are organizing for a huge national march, with community leaders and indigenous authorities in our communities and from surrounding communities. I want to send this message to all the supporters of our struggle. Tell them we continue to fight because mining companies everywhere use the same tactics of threats and fear. We can unite and with that strength we can resist. We won’t let them destroy us. We must protect our Mother Earth.”

(The Canadian Goldcorp Corporation is strip mining for gold in San Miguel Ixtahuacán, Guatemala, which is harming the environment and the health of the local population.)

IPHU students from Guatemala, Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Spain and other countries shared information about the social and environmental destruction in area communities. At one meeting, the leaders are making plans for Earth Day; at another, they discuss the rights to information, to resist and to health care, and mining’s impact on society.

Marvin, from Venezuela, urged people to listen to the voices of the native peoples and seconded a proposal to send a communiqué to the Human Rights Commission to tell the world about the case of San Miguel Ixtahuacán.

Rosario, from Bolivia, recommended that social organizations publicize the issue to support the anti-mining cause. She shared a statement issued by the Latin American Women’s Union in March 2010 in Guatemala titled “Beyond the Challenge: Women, Mining and Human Rights,” which calls for respect for the International Labour Organization’s resolution ordering a halt to mining activity in San Miguel Ixtahuacán and San Juan Sacatepéquez and the suspension of licenses granted in Izabal, all in Guatemala.

Byron, from Ecuador, said that just as in Guatemala, mining operations and exploration are also underway in his country. He said that people living in places where companies want to strip mine should learn about how disastrous it is and fight for their rights to the land and to health. He also suggested that people in the IPHU could form a communications network that would share with the world experiences, opinions, expectations, complaints and violations regarding open-pit mining.

Claudemir, from Brazil, asked the question: What happens if mining companies bring in roads, schools and economic programmes, but the water in the area runs out because the strip mine takes it all? He feels that if there is no water, there is no life; therefore, it does not make sense to let these transnational corporations operate in this region or in other parts of the world.

Leonel, from Mexico, said they cried when the women fighting to defend their land talked about the things that had happened to them—the deaths, the persecution, divided families, cracks in the walls of their homes from the explosives used in the mine, cyanide and mercury poisoning, and how the affected communities are being controlled with the complicity of the authorities. This is why it is important to publicize this struggle and to take concrete action to unite the native peoples of Latin America in condemning the transnational mining corporations that are laying waste to our planet. On Earth Day, we should all take to the streets of Guatemala to shout “No multinational mining!”

Meanwhile, the IPHU students continue to analyze and discuss intercultural health and primary health care in the communities of Guatemala.

Chimaltenango 2010

Patricio Matute García

EQUIPO COMUNICÁNDONOS